Chapter 1

|

I |

n the beginning was the Word—also known as a very big bang marvelous sort of Expletive—a circumstance wherein God created the universe.

He made light and stars and constellations and galaxies and planets, and a certain very particular lump of matter called earth, which He populated—heavens and firmament—with teeming curious creatures. These included, among others, trilobites and baboons, porcupines and ferrets, pigeons and bumblebees, manatees and kangaroo, the duck and the duckbill platypus, and of course, the upright great apes called humans.

The latter, created most in His Image, immediately proceeded to “ape” for all they were worth—in other words, to create in turn—and were directly responsible for the manufacture of virtue and taste, style and erudition, and henceforth the knowledge of Good and Evil as pertaining to fashionable trifles suitable for adornment during a preening exhibition called the London Season.

Also created were gossip and dowry, followed by courtship and matrimony, and then tedium and ennui. Last, and not least, came the acquired taste for trimming hedges in the French style, and the secret delight in sanguine scenes of murderous dread, gothic terrors, and dark rending romance, particularly in the young female of the species, as perpetuated by a certain literary female by the name of Mrs. Radcliffe.

To provide this teeming Creation with some modicum of order and supervision, God also created angels and demons and seraphim and nephilim, and occasional great serpents and dragons, all of which he initially imbued with common sense—the one precious and infinitely rare faculty that the rest of the Creation was sorely lacking.

For, what is order without common sense, but Bedlam’s front parlor? What is imagination without common sense, but the aspiration to out-dandy Beau Brummell with nothing but a bit of faded muslin and a limp cravat? What is Creation without common sense, but a scandalous thing without form or function, like a matron with half a dozen unattached daughters?

And God looked upon the Creation in all its delightful multiplicity, and saw that, all in all, it was quite Amiable.

There was but one minor problem.

Common sense was not as common as the Deity might wish for. Indeed, not even angelic choirs were entirely free of a certain vice known as silliness.

And if the very angels were thus flawed, then what might one expect of innocent young ladies?

|

S |

peaking of innocent young ladies—behold our heroine, Catherine Morland. Admittedly, no one who had ever seen Catherine in her infancy would have supposed her born to be an heroine. Her situation in life, the character of her father and mother, her own person and disposition, were all equally against her.

In one inconsequential detail alone was she at all a standout—indeed, it was such a very peculiar and supernatural thing that some might venture to question its validity. For, not unlike the saintly Joan of Arc of old, our Catherine could hear the voices and speech of angels and demons, and had the innate ability to understand their language, both profane and divine. Furthermore, she was also able to see them as corporeal beings, in all their bright glory and terrifying aspect. Of course, for a very long time she was blessedly unaware of the fact.

But, gentle Reader, we are getting ahead of ourselves.

|

A |

s is rather appropriate for a young girl who was one day to commune with the otherworldly, her father was a clergyman. Without being neglected, or poor, he was a very respectable man, though his name was Richard[1]—and he had never been handsome. He had a considerable independence besides two good livings—and he was not in the least addicted to locking up his daughters.

Her mother was a woman of useful plain sense, with a good temper, and, what is more remarkable, with a good constitution. She had three sons before Catherine was born; and instead of dying in bringing the latter into the world, as anybody might expect, she still lived on—lived to have six children more—to see them growing up around her, and to enjoy excellent health herself. A family of ten children will be always called a fine family, where there are heads and arms and legs enough for the number; but the Morlands had little other right to the word, for they were in general very plain. And Catherine, for many years of her life, was as plain as any, not to mention completely deaf to any dulcet tones of the angel choirs in the ether all around.

She had a thin awkward figure, a sallow skin without colour, dark lank hair, and strong features. Her eyes were not sapphire like the summer skies; nor her lips like ripe cherries (though occasionally this could be said of her nose after she had been outside on a particularly frosty winter day). Neither were her cheeks like roses (tea or floribunda), nor the tone of her voice like tinkling bells, but more often like a foghorn coming off a very distant waterway (their domicile being nowhere near the coast) when she rolled about the grass screaming with rather gargantuan laughter among her younger siblings;—so much for her person; and not less unpropitious for heroism seemed her mind.

She was fond of all boy’s plays, and greatly preferred cricket not merely to dolls, but to the more heroic enjoyments of infancy, nursing a dormouse,[2] feeding a canary-bird, or watering a rose-bush. Indeed she had no taste for a garden (nor had she any idea of the extent to which gardens were filled to bursting with all manner of angels, paunchy cherubs, and other metaphysical spirits and fae). And if she gathered flowers at all, it was chiefly for the pleasure of mischief (indeed, a mild bit of demonic inclination here—but, rest assured, dear Reader, quickly overcome and conquered as a youthful personality deficit)—at least so it was conjectured from her always preferring those which she was forbidden to take.

Such were her propensities. Her abilities were quite as extraordinary. She never could learn or understand anything before she was taught; and sometimes not even then, for she was often inattentive, and occasionally stupid. Her mother was three months in teaching her only to repeat the “Beggar’s Petition”; and after all, her next sister, Sally, could say it better than she did. Not that Catherine was always stupid—by no means; she learnt the fable of “The Hare and Many Friends” as quickly as any girl in England (and since the days of her metaphysical ignorance were numbered, there was just a hint of Ancient Hebrew, hovering, one might say, at the tip of the tongue, and quite ready to be thoroughly absorbed and fathomed).

Her mother wished her to learn music; and Catherine was sure she should like it, for she was very fond of tinkling the keys of the old forlorn spinnet; so, at eight years old she began. She learnt a year, and could not bear it (and neither could most of the household angelic sprites who, upon the first tinkling sound, fled the music room in greater haste and dread than had they been chastised by the archangels themselves). Thankfully, Mrs. Morland, who did not insist on her daughters being accomplished in spite of incapacity or distaste, allowed her to leave off (for which, little did she know, but the good matron received a host of supernatural blessings, including a permanent guarantee against curdled milk on the premises). The day which dismissed the music-master was one of the happiest of Catherine’s life. That same happy day was marked by hosannas and seraphim making particular celebratory music in the spheres.

Her taste for drawing was likewise not superior; though whenever she could obtain the outside of a letter from her mother or seize upon any other odd piece of paper, she did what she could in that way, by drawing houses and trees, hens and chickens, and an occasional monstrous duck, all very much like one another. Writing and accounts she was taught by her father; French by her mother: her proficiency in either was not remarkable, and she shirked her lessons in both whenever she could (for, as can be seen, there was as yet no dulcet angelic voice whispering in her ear and guiding her toward prudence).

What a strange, unaccountable character!—for with all these symptoms of profligacy at ten years old, she had neither a bad heart nor a bad temper, was seldom stubborn, scarcely ever quarrelsome, and very kind to the little ones, with few interruptions of tyranny. She was moreover noisy and wild, hated confinement and cleanliness, and loved nothing so well in the world as rolling down the green slope at the back of the house.

Such was Catherine Morland at ten. And precisely at such a youthful junction, an event of arcane magnitude occurred that, with a single blow of fate, transformed our mundane heroine into a metaphysical prodigy.

Catherine, merrily skipping down the above-mentioned green slope in the back, did not notice where her foot was placed. She tripped and fell; her head came in contact with a rocky lump of earth. And just as a freshly painful lump immediately appeared at the back of her head—a lump not unlike numerous other lumps she had received previously upon many similar circumstances—in that very same moment Catherine felt and heard a crack . . . It was as though her skull was curiously cracked open like a walnut, and something opened inside her head.

The next moment was a veritable flood of senses. Sight and sound were suddenly more pungent; colors rippled and doubled as though imbued with a secret rainbow; sunlight fractured into splinters of magical glass, and sweet music filled the air from all directions.

And then came the angel voices!

Oh, how they sang! Light, clean soprano and sweet alto, and all things in-between! How pure and far-ranging were their tones, how amazing the echoes of cathedral richness in the grand open expanse!

Catherine stood up, forgetting all about the painfully stinging lump in her head, the grass staining her knees, and merely lingered with wonder, taking it all in, listening, listening, looking . . .

And as she looked, she began to see the sources of the divine chorus, the many tiny figures of light, like distant fireflies, sparkling akin to disembodied candle flames among the grass and the flowers and among the leaves of the trees.

“Oh dear!” said Catherine, “What—who are you?”

In response one tiny figure, radiating tangible warmth and kindness, sprang up like a shooting star, or possibly a dragonfly, and darted to hang in the air just an inch before Catherine’s nose.

“Dearest child, we are angels, of course!” it replied, looking at her with infinite love.

Catherine blinked, and the next moment they came to her, shooting stars from all directions, a moving cloud of fiery hummingbirds—nay, tiny winged beings—and they exclaimed in sweet voices, “Behold! At last, she can see!”

From this remarkable point forward, things were rather different, for, wherever she went, Catherine was never again to be alone. Her world had shifted and expanded, she saw, and heard, and as a result paid better attention, and thus it was that her life had entered the next stage—which is inevitable when everything is to be accompanied by faithful commentary and a remarkable audience.

|

A |

t fifteen, appearances were mending, not only of the world around her, but also of Catherine herself.

Now that angels filled every nook and crevice and whispered perfectly reasonable and wise advice in her ear, it did not at all prevent her from beginning to curl her hair and longing for balls. Her complexion improved, her features were softened by plumpness and colour, her eyes gained more animation, and her figure more consequence. Her love of dirt gave way to an inclination for finery, and she grew clean as she grew smart. She had now the pleasure of sometimes hearing her father and mother remark on her personal improvement.

“Catherine grows quite a good-looking girl—she is almost pretty today,” were words which caught her ears now and then, in addition to various angelic whispers and exclamations of delight as to her character growth as a heroine-to-be; and how welcome were the sounds of approval at last from both parents and seraphim!

To look almost pretty is an acquisition of higher delight to a girl who has been looking plain the first fifteen years of her life than a beauty from her cradle can ever receive. And to be almost perfectly good was the kind of heavenly approbation that had no earthly match of any kind.

Mrs. Morland was a very good woman in her turn, and wished to see her children everything they ought to be. But her time was so much occupied in lying-in and teaching the little ones, that her elder daughters were inevitably left to shift for themselves; and it was not very wonderful that Catherine, who had by nature nothing heroic about her (except for the arsenal of angels), should prefer cricket, baseball,[3] riding on horseback, and running about the country at the age of fourteen, to books—or at least books of information—for, provided that nothing like useful knowledge could be gained from them, provided they were all story and no reflection, she had never any objection to books at all. Whilst from ten onward she was in training for a mystical prodigy, from fifteen to seventeen she was in training for a heroine—reading all such works as heroines must to supply their memories with those quotations which are so serviceable and so soothing in the vicissitudes of their eventful lives.

From Pope, she learnt to censure those who

“bear about the mockery of woe.”

From Gray, that

“Many a flower is born to blush unseen,

“And waste its fragrance on the desert air.”

From Thompson, that—

“It is a delightful task

“To teach the young idea how to shoot.”

And from Shakespeare she gained a great store of information—amongst the rest, that—

“Trifles light as air,

“Are, to the jealous, confirmation strong,

“As proofs of Holy Writ.”

That

“The poor beetle, which we tread upon,

“In corporal sufferance feels a pang as great

“As when a giant dies.”

And that a young woman in love always looks—

“like Patience on a monument

“Smiling at Grief.”

So far her general improvement was sufficient—and in many other points she came on exceedingly well; for though she could not write sonnets, she brought herself to read them (and recite a few of them out-loud to throw off suspicion, in case of particularly pointed angelic argument). And though there seemed no chance of her throwing a whole party into raptures by a prelude on the pianoforte, she could listen to other people’s performance with very little fatigue. Furthermore, an angel could always be relied upon if needed to pull open her drooping eyelids.

Her greatest deficiency was in the pencil—short of stick figures and monstrous ducks, she had no notion of drawing—not enough even to attempt a sketch of her lover’s profile, that she might be detected in the design. There she fell miserably short of the true heroic height, and it was something for which no heavenly reinforcement could compensate. At present she did not know her own poverty, for she had no lover to portray. She had reached the age of seventeen, without having seen one amiable youth who could call forth her sensibility, without having inspired one real passion, and without having excited even any admiration but what was very moderate and very transient, much less gothic or medieval.

This was strange indeed! But strange things may be generally accounted for if their cause be fairly searched out. There was not one lord in the neighbourhood; no—not even a baronet. There was not one family among their acquaintance who had reared and supported a boy accidentally found at their door—not one young man whose origin was unknown. Her father had no ward, and the squire of the parish no children. Even the servants had no sufficiently ruddy cheeked and comely young son to mysteriously pass by her in the green, while leading a nobly saddled mare (nay, a proper stallion!) or carrying a mighty load of firewood worthy of someone endowed with Herculean or knightly upper limbs.

But when a young lady is to be an heroine, the perverseness of forty surrounding families cannot prevent her. Neither can large oceanic-bound landmasses, arid deserts or frightful moors. Indeed, not even Heaven itself. Something must and will happen to throw a hero in her way.

Mr. Allen, who owned the chief of the property about Fullerton, the village in Wiltshire where the Morlands lived, was ordered to Bath for the benefit of a gouty constitution—and his lady, a good-humoured woman, fond of Miss Morland, and probably aware that if adventures will not befall a young lady in her own village, she must seek them abroad, invited her to go with them. Mr. and Mrs. Morland were all compliance, and Catherine all happiness.

And the angels? For mysterious reasons they were in a bit of a tumult!

Chapter 2

|

I |

n addition to what has been already said of Catherine Morland’s personal and mental endowments, when about to be launched into all the difficulties and dangers of a six weeks’ residence in Bath (and a possible heroic grand adventure), it may be stated that her heart was affectionate; her disposition cheerful and open, and—discounting her tendency to “converse” out loud, without conceit or affectation of any kind. Her manners were just removed from the awkwardness and shyness of a girl; her person pleasing, and, when in good looks, pretty—and her mind about as ignorant and uninformed as the female (or for that matter, male) mind at seventeen usually is. In short, a mind ready to be molded by grander forces, be it of Heavenly, or, God forbid, of a rather lower variety.

But once again, dear Reader, we are getting somewhat ahead of ourselves. . . .

When the hour of departure drew near, the maternal anxiety of Mrs. Morland will be naturally supposed to be most severe. A thousand alarming presentiments of evil to her beloved Catherine from this terrific separation must oppress her heart and drown her in tears for the last days of their being together (while angels all over the domicile went into veritable flurries of sympathetic agitation, occasionally knocking down minor objects on shelves and raising inexplicable drafts in closed windowless rooms). And important advice must of course flow from wise maternal lips in their parting conference in her closet (closets being the obligatory locales for such). Cautions against the violence of noblemen who delight in forcing young ladies away to some remote farm-house, must, at such a moment, relieve the fullness of her heart. Who would not think so?

But Mrs. Morland knew so little of lords and baronets, that she entertained no notion of their general mischievousness, and was wholly unsuspicious of danger to her daughter from their machinations. Her cautions were confined to the following points. “I beg, Catherine, you will always wrap yourself up very warm about the throat, when you come from the rooms at night; and I wish you would try to keep some account of the money you spend; I will give you this little book on purpose—Pray, are you listening, child? You appear so distracted yet again. Were you just talking to the wardrobe chest? Oh dear . . .”

“Not at all, mama,” replied Catherine reasonably, and avoided bestowing a glance at the three tiny angelic figures practically doing cartwheels on top of the chest, in their attempt to capture her attention.

Soon enough Mrs. Morland left the room for a moment, in order to fetch some pins that the maid apparently left in the parlor. And Catherine allowed herself to look directly at the heavenly beings. “Goodness, what is it?”

“Oh, Catherine!” exclaimed one tiny figure of light—tiny indeed, for he (or she?) was no greater than three inches in height, including folded wingspan. “Catherine, you are hereby placed in gravest danger!”

And the other two echoed him in tinkling voices, “Catherine, oh, Catherine, oh, woe! Danger!”

“What? What do you mean?”

“Oh!” cried another tiny angel. “Whatever you do, you must not go away!”

“No, dear child, you must not! This trip bodes dire and eternal misfortune!”

“But—” said Catherine, sitting down on the edge of her bed. “But how awful! It is Bath! How can I not go? And it is to be with Mrs. Allen, she is so kind to have invited me, and—what in the world could be so horridly dangerous?”

In response the angels started flittering about terribly, their luminescent figures growing in brightness, which happened frequently when they were in a state of agitation.

Eventually one of them collided with a candlestick, and Catherine had to jump up in a hurry to catch the burning candle with amazing dexterity of one hand, while snatching a floundering winged being with another.

“Oh! Fire! Do be careful, Lawrence!” cried the other two, jumping up and down, then promptly collided with one another.

“Upon my word! This is quite ridiculous!” Catherine said, holding an angel in the palm of her hand and glaring at two more sliding around on her bedspread. “I insist you tell me what is the matter, at once! And for the hundredth time, keep away from burning flames!”

In her hand, the angel’s golden glow dimmed a little to a warm peach and then soft mauve. The being settled firmly on her palm, and put its head between two tiny arms, in a gesture of infinite regret. “I am afraid, dear Catherine, I cannot.”

“Cannot what?”

“He cannot speak, he may not answer,” piped in the others. “Indeed, none of us can tell you. We can only warn you and entreat you not to go.”

Catherine let out a long breath of frustration. “This is quite silly. How as I supposed to do or not do things, go or not go places, all without a good reason? And especially when you first frighten me to death and then refuse to explain?”

“We can only ask you to trust us—”

“Wait!” said Catherine, as though awakening out of an extended sleep. “And since when do you have given names? Lawrence?”

“It is indeed I,” replied the little being on her palm.

“So you mean to tell me that for all these months I could have been referring to each one of you in a civil manner, instead of resorting to idiocy such as Splatterplop and Fumblehead—and—”

“I am Terence,” said one of the two on her bed.

“And you may call me Clarence.”

“Well, criminy!” said Catherine.

“Not Criminy, I am Cla—”

At which point Terence touched the other gently.

“We were not allowed to utter our names before this day,” said Lawrence, folding his/her/its little hands together and fluttering its wings suddenly like a butterfly of pure light.

“Before this day? What changed? It is a Tuesday.”

“Grave danger,” said Clarence.

“Today we were instructed to guard you,” said Terence.

“That is, we guard everyone, but from this point on we must guard you with particular care,” added Lawrence.

“More than you already guard me, day and night?”

“More than imaginable,” said Lawrence. “For today you are considering leaving home for the first time and venturing into the world, and when and once you do, it becomes inevitable that you will be assailed—”

“Attacked!”

“Besieged and sorely tempted!

“Surrounded and stormed and thoroughly tested!”

“Fallen upon from all sides!”

“And for that reason we are given the sternest and most solemn instruction from On High, to watch over you and protect you with all our own strength!”

“All our fortitude!”

“Our loyalty!”

“Our love!”

“But—” said Catherine, “Yes, that is, I mean—thank you kindly from my heart, indeed—but, why? And who in the world will be attacking me? Why me? What is this dreadful danger?”

But all three angels hung their heads and would not speak. Several long moments passed, while Catherine considered this unbelievable turn of events while fiddling nervously with a bit of lace. Then, with a firm sense of resolve, she sat up straight, and announced, not unlike a proper heroine: “Since you will not explain, I am obviously meant to go and face this danger directly. Besides—it’s adventure! It’s Bath!”

One by one, the angels sadly looked up.

One nodded, whispering, “Oh dear . . . We knew you would decide thus.”

“Please,” tried Lawrence once again, glowing in the palm of her hand. “Catherine, oh, Catherine, mayhap you might still change your mind?”

But because the angel knew very well they were dealing with an heroine, it/she/he resigned himself to a heavenly sigh.

|

M |

eanwhile the trip preparations must but continue. Catherine’s sibling Sally, or rather Sarah (for what young lady of common gentility will reach the age of sixteen without altering her name as far as she can?), must from situation be at this time the intimate friend and confidante of her sister. At least, such was the assumption (though Catherine already had a veritable regiment of heavenly confidants at her disposal). It is remarkable, however, that Sarah neither insisted on Catherine’s writing by every post, nor exacted her promise of transmitting the character of every new acquaintance, every interesting conversation that Bath might produce. She did however request chartreuse ribbon, such as was rumored to be particularly fashionable.

Everything indeed relative to this important journey was done, on the part of the Morlands, with a degree of moderation and composure—excepting a few inexplicable flurries of drafts, moving curtains, and strangely teetering figurines on shelves and mantels. All preparation seemed more consistent with the common feelings of common life, than with the tender emotions which the first separation of an heroine from her family ought always to excite.

Her father, instead of giving her either nothing at all or an unlimited order on his banker, gave her only ten guineas, and promised her more when she wanted it.

Under these unpromising auspices, the parting took place, and the journey began. Catherine, with at least half a dozen glowing angelic figures hovering overhead, sat in the carriage seat near Mrs. Allen who, she noticed, had a few angels of her own (but was perfectly oblivious of them, as everyone else in the world but Catherine seemed to be). For hours Catherine dearly kept her eyes away from the supernatural presences and bravely ignored them practically crawling all over Mrs. Allen’s bonnet, not to mention their exclamations and sighs and repeated cries of “Beware! Oh dear child, what frightful harm might befall you any moment!”

Their agitation got so dire and tedious at one point that Catherine had to mutter, “Shush!” and disguise it with a cleverly timed sneeze into a handkerchief (which sent Terence—or possibly Lawrence—flying into the brocade curtain).

But despite the warnings, the trip was performed with suitable quietness and uneventful safety. Neither robbers nor tempests befriended them, nor was there one lucky carriage overturn to introduce them to the hero. There were no romantic masked highwaymen in the moonlight (indeed, the moon itself was in a thin new crescent state, thus refusing to cooperate with a proper heroic scenario).

Nothing more alarming occurred than a fear, on Mrs. Allen’s side, of having once left her clogs behind her at an inn (a fine establishment which was neither haunted nor occupied by a band of cutthroats—though there were rumors of a monstrous flying fowl observed in the neighborhood, pronounced in whisper to be none other than the Brighton Duck[4]), and that fortunately proved to be groundless.

They arrived at Bath. Catherine was all eager delight—her eyes were here, there, everywhere, for once naturally ignoring the heavenly host.

They approached Bath’s fine and striking environs, and afterwards drove through those streets which conducted them to the hotel. She was come to be happy, regardless of angelic warnings of decidedly silly and unfounded doom, and she felt happy already.

They were soon settled in comfortable lodgings in Pulteney Street.

|

I |

t is now expedient to give some description of Mrs. Allen, that the astute Reader may be able to judge in what manner her actions will hereafter tend to promote the general distress of the work, and how she will, probably, contribute to reduce poor Catherine to all the desperate wretchedness of which a last volume[5] is capable—whether by her imprudence, vulgarity, or jealousy—whether by intercepting her letters, ruining her character, or turning her out of doors. For, surely the angels cried such dire warning in regard to none other than Mrs. Allen?

Or, quite possibly, not. . . .

Mrs. Allen was one of that numerous class of females, whose society can raise no other emotion than surprise at there being any men in the world who could like them well enough to marry them. She had neither beauty, genius, accomplishment, nor manner. The air of a gentlewoman, a great deal of quiet, inactive good temper, and a trifling turn of mind were all that could account for her being the choice of a sensible, intelligent man like Mr. Allen.

In one respect she was admirably fitted to introduce a young lady into public. She was as fond of going everywhere and seeing everything herself as any young lady could be (only unhindered by supernatural awareness). Dress was her passion. She had a most harmless delight in being fine. And our heroine’s entree into life could not take place till after three or four days had been spent in learning what was mostly worn (not chartreuse, unfortunately for Sarah), and her chaperone was provided with a dress of the newest fashion. This was done to the accompaniment of angelic delight and running commentary in tinkling voices, on the fabric, pattern, and color—who could but imagine the angels were so well versed in style and decoration? Catherine could not help but smile when she saw Clarence—or possibly Terence—getting tangled in piles of muslin and ribbon at the shops they visited. Meanwhile, the poor shop girls and seamstresses nearly lost their minds at so much peculiar displacement of objects, bolts and skeins, at all the ceaseless fluttering and unraveling of thread that accompanied Catherine’s visits to their fine establishments.

As for those frightful warnings of imminent danger? Blessedly, so far, none of it materialized.

Catherine too made some purchases herself (including a ribbon for Sarah—sunflower-golden, in place of out-of-vogue chartreuse), and when all these matters were arranged, the important evening came which was to usher her into the Upper Rooms.

Her hair was cut and dressed by the best hand, her clothes put on with care, and both Mrs. Allen and her maid declared she looked quite as she should do. The heavenly beings echoed them heartily. One of them exhibited enthusiastic approbation to the effect of falling into an open box of powder, fluttering its tiny wings and raising up such a puff-cloud that Mrs. Allen started to sneeze and had to be tended to by the maid all over again.

With such encouragement, Catherine hoped at least to pass uncensured through the crowd. As for admiration, it was always very welcome when it came, but she did not depend on it.

|

M |

rs. Allen was so long in dressing that they did not enter the ballroom till late. The season was full, the room crowded, and the two ladies squeezed in as well as they could. As for Mr. Allen, he repaired directly to the card-room—accompanied by one solitary tiny glowing guardian angel hovering over his head like a determined personal hummingbird—and left them to enjoy a mob by themselves.

Two dozen or so tiny angelic figures fluttering above Catherine’s impeccably sculpted hair, immediately dispersed about the large crowded expanse to scout and investigate all nooks for signs of menace. And yet, unless the threat came in the form and size of gnats or moths, Catherine wondered, what good did it to do to check behind candelabras and curtain valances? She did note however that at least two angels remained in her vicinity at all times. Also, there were a number of other angels surrounding other persons in the room, in droves of varying number—angels that had already been present in the room before they arrived. (Sometimes Catherine forgot that other people, indeed everyone, had their own heavenly guardians. It is but that she seemed to attract and collect them inordinately, since they knew she could see them and it seemed to please them greatly.)

With more care for the safety of her new gown than for the comfort of her protégée, Mrs. Allen made her way through the throng of men by the door, as swiftly as the necessary caution would allow. Catherine kept close at her side, and linked her arm firmly within her friend’s so as not to be separated. But to her utter amazement she found that to proceed along the room was by no means the way to disengage themselves from the crowd. It seemed rather to increase as they went on, whereas she had imagined that when once fairly within the door, they should easily find seats and be able to watch the dances with perfect convenience.

But this was far from being the case. Though by unwearied diligence they gained even the top of the room, their situation was just the same; they saw nothing of the dancers but the high feathers of some of the ladies (and Catherine noted angels perched on top of quite a few of them). Still they moved on—something better was yet in view; and by a continued exertion of strength and ingenuity they found themselves at last in the passage behind the highest bench. Here there was something less of crowd than below; and hence Miss Morland had a comprehensive view of all the company beneath her, and of all the dangers of her late passage through them.

It was a splendid sight, and she began, for the first time that evening, to feel herself at a ball. She longed to dance, but she had not an acquaintance in the room. Mrs. Allen did all that she could do in such a case by saying very placidly, every now and then, “I wish you could dance, my dear—I wish you could get a partner.” For some time her young friend felt obliged to her for these wishes; but they were repeated so often, and proved so totally ineffectual, that Catherine grew tired at last, and would thank her no more.

A tiny voice sounded in her ear, “Dear child, be consoled by the fact that so far you have been unnoticed by any malevolent ones!” It was either Clarence or Lawrence, who found a sitting spot on one of her puffed sleeves. “Indeed, dancing, though pleasant, is far from being as universally enjoyable as one might suppose! Fie, dancing!”

“And how would one such as yourself know?” whispered Catherine at her sleeve, pretending to fan herself. “Isn’t dancing a mundane frivolity?”

“Not in the least,” said the angel. “For, we dance and rejoice when Good is accomplished, just as well as we weep and mourn when Evil is done.”

“Then you must spend all your time waltzing and weeping simultaneously,” mused Catherine. “What an oddity of existence!”

There was a tinkle of angelic laughter as another tiny being whispered in her other ear, “Oh goodness, no! Only the Almighty has that divine and paradox ability; we necessarily take turns doing one and then the other! For example, today, this moment, I am directed only to laugh and dance in joy at all the Goodness in the world. Lawrence, meanwhile, is away, doing his weekly share of mourning at the Suffering. But, fear not; he will return shortly, for a week’s worth of mourning is but a blink of an eye in heavenly time.”

“I thought you were Lawrence.”

“Oh no, I am Terence.”

“And I am Clarence,” came from the other ear.

“Of course, I am sorry . . .” Catherine rushed to reply, though, to be honest, she mostly had no idea which of the angels she was talking to at any given moment.

“What was that, dear?” said Mrs. Allen. “Did you say something? No? Well indeed, I wish you could dance—I wish you could get a partner. Otherwise, you would not feel this regrettable need to hold discourse with your fan, you poor thing,” she added to herself.

They were not long able, however, to enjoy the repose of the eminent spot they had so laboriously gained. Everybody was shortly in motion for tea, and they must squeeze out like the rest. Catherine began to feel something of disappointment. She was tired of being continually pressed against by people whose faces possessed nothing to interest, and with all of whom she was so wholly unacquainted that she could not relieve the irksomeness of imprisonment by the exchange of a syllable with any of her fellow captives.

When they at last arrived in the tea-room, she felt yet more the awkwardness of having no party to join, no acquaintance to claim, no gentleman to assist them (only angels peeking around teacups and saucers). They saw nothing of Mr. Allen; and after looking about them in vain for a more eligible situation, were obliged to sit down at the end of a table, at which a large party were already placed, without having anything to do there, or anybody to speak to, except each other.

And just for a single moment Catherine had an unsuitable thought—what if such pointed lack of acquaintance was the secret result of her heavenly guardians keeping them all away?

Mrs. Allen congratulated herself, as soon as they were seated, on having preserved her gown from injury. “It would have been very shocking to have it torn,” said she, “would not it? It is such a delicate muslin. For my part I have not seen anything I like so well in the whole room, I assure you.”

“How uncomfortable it is,” whispered Catherine, “not to have a single acquaintance here!” And she moved her elbow slightly to push Terence, or Clarence, several inches away from the peril of falling onto a pastry dish.

“Try not to flap your wings so,” she added, as the angel regained its balance on the gilded china rim.

“Yes, my dear,” replied Mrs. Allen, with perfect serenity, “it is very uncomfortable indeed. That is, no—what was it that you said? Wings? Oh dear! Am I flapping something? Is something torn?”

“Nothing, I mean, rings! What lovely rings that lady has!” Catherine hurried to speak.

Ms. Allen was mollified.

Catherine continued, steering the conversation further: “What shall we do? The gentlemen and ladies at this table look as if they wondered why we came here—we seem forcing ourselves into their party.”

“Aye, so we do. That is very disagreeable. I wish we had a large acquaintance here.”

“I wish we had any—it would be somebody to go to.”

“Very true, my dear; and if we knew anybody we would join them directly. The Skinners were here last year—I wish they were here now.”

“Had not we better go away as it is? Here are no tea-things for us, you see.”

“No more there are, indeed. How very provoking! But I think we had better sit still, for one gets so tumbled in such a crowd! How is my head, my dear? Somebody gave me a push that has hurt it, I am afraid. Even now I feel something pulling, indeed—”

Catherine enacted a meaningful stare at the tiny glowing figure that managed to land on Mrs. Allen’s feather-spangled crown and was duly caught on a hairpin.

“No, indeed, it looks very nice. But, dear Mrs. Allen, are you sure there is nobody you know in all this multitude of people? I think you must know somebody.”

“I don’t, upon my word—I wish I did. I wish I had a large acquaintance here with all my heart, and then I should get you a partner. I should be so glad to have you dance. There goes a strange-looking woman! What an odd gown she has got on! How old-fashioned it is! Look at the back.”

After some time they received an offer of tea from one of their neighbours; it was thankfully accepted, and this introduced a light conversation with the gentleman who offered it, which was the only time that anybody spoke to them during the evening, till they were discovered and joined by Mr. Allen when the dance was over.

“Well, Miss Morland,” said he, directly, “I hope you have had an agreeable ball.”

“Very agreeable indeed,” she replied, vainly endeavouring to hide a great yawn.

“I wish she had been able to dance,” said his wife; “I wish we could have got a partner for her. I have been saying how glad I should be if the Skinners were here this winter instead of last; or if the Parrys had come, she might have danced with George Parry. I am so sorry she has not had a partner!”

“We shall do better another evening I hope,” was Mr. Allen’s consolation.

The company began to disperse when the dancing was over—enough to leave space for the remainder to walk about in some comfort; and now was the time for a heroine, who had not yet played a very distinguished part in the events of the evening, to be noticed and admired. Oh, if only they could see how many shining angels ringed her head in a joyful halo of brightness—but no, of course no one could see it, and thus the heroine continued to endure enforced anonymity.

Every five minutes, by removing some of the crowd, gave greater openings for her charms. She may not have been observed, but surely she was now seen by many young men who had not been near her before. Not one, however, started with rapturous wonder on beholding her. No whisper of eager inquiry ran round the room, nor was she even once called a divinity by anybody, despite the supreme irony of having so much of the divine fluttering about her. Yet Catherine was in very good looks, and had the company only seen her three years before, they would now have thought her exceedingly handsome.

She was looked at, however, and with some admiration; for, in her own hearing, two gentlemen pronounced her to be a pretty girl. Such words had their due effect; Catherine immediately thought the evening pleasanter than she had found it before—her humble vanity was contented. She felt more obliged to the two young men for this simple praise than a true-quality heroine would have been for fifteen sonnets in celebration of her charms, and went to her chair in good humour with everybody.

She was thus perfectly satisfied with her share of public attention, while the angels, of course were perfectly satisfied with the fortunate lack of threat to her person.

All in all, things had gone tolerably well.

Chapter 3

|

E |

very morning now brought its regular duties—shops were to be visited; some new part of the town to be looked at; and the pump-room to be attended, where they paraded up and down for an hour, looking at everybody and speaking to no one. Everywhere they went, the angels spread about like fireflies, winking among stylish scenery and even more stylishly attired pedestrians. Catherine heard their melodious voices declaring safety and pronouncing various unlikely spots such as flower vases and decorative marble pedestals to be free of malice.

The wish of a numerous acquaintance in Bath was still uppermost with Mrs. Allen, and she repeated it after every fresh proof, which every morning brought, of her knowing nobody at all. Catherine was beginning to think her unseemly idea about angelic intervention was not far off the mark.

They made their appearance in the Lower Rooms; and here fortune was more favourable to our heroine. The master of the ceremonies introduced to her a very gentlemanlike young man as a partner; his name was Tilney.

As soon as the introduction took place, in that exact moment, there was a minor commotion behind Catherine’s ear, as Lawrence, or possibly Terence, exclaimed, “Oh dear! Oh, Catherine! Danger! Oh—”

But of course our heroine did not, and indeed could not—or possibly would not—pay any heed, since here was the dear opportunity, at last, to make a proper new acquaintance.

Mr. Tilney seemed to be about four or five and twenty, was rather tall, had a pleasing countenance, a very intelligent and lively eye, and, if not quite handsome, was very near it. His address was good, and Catherine felt herself in high luck. There was little leisure for speaking while they danced (and the angels—being at least half a dozen in number, on each side, and talking all at once in both of Catherine’s ears—did present an inordinate aural challenge).

But when they were seated at tea, she found him as agreeable as she had already given him credit for being. He talked with fluency and spirit—and there was an archness and pleasantry in his manner which interested, though it was hardly understood by her.

“Be careful, oh do be careful of this gentleman, dear child! You know nothing about him!” exclaimed one particularly noisome heavenly creature at some point, balancing on the handle end of a teaspoon, so that she had to press down the other end for balance or have it go flying across the room (and possibly into the eye of the dignified matron or any one of her three young daughters across the table).

“Shush! Enough!” said Catherine to the angel, whispering this admonition while moving her lips as little as possible. Then, bending forward, she pretended to blow on her tea.

Seeing Mr. Tilney’s bemused attention to her mutterings and movements, she hurried to amend, “That is, I mean, cough! Cough!” And she politely cleared her throat to reinforce her point. “Goodness, the tea is rather hot.”

But Mr. Tilney continued to observe her with an expression she could not fathom.

After chatting some time on such matters as naturally arose from the objects around them, he suddenly addressed her with—“I have hitherto been very remiss, madam, in the proper attentions of a partner here; I have not yet asked you how long you have been in Bath; whether you were ever here before; whether you have been at the Upper Rooms, the theatre, and the concert; and how you like the place altogether. I have been very negligent—but are you now at leisure to satisfy me in these particulars? If you are I will begin directly.”

“Tell him nothing!” exclaimed Clarence, or Terence.

“No indeed! you must remain very circumspect in what you say!” echoed Lawrence—or—or someone . . . Catherine was dearly annoyed at this point; she simply wanted to attend carefully to this pleasant gentleman.

“You need not give yourself that trouble, sir,” she therefore said, flatly ignoring the angelic clamor.

“No trouble, I assure you, madam.” Then forming his features into a set smile, and affectedly softening his voice, he added, with a simpering air, “Have you been long in Bath, madam?”

“About a week, sir,” replied Catherine, trying not to laugh.

“Really!” with affected astonishment.

“Why should you be surprised, sir?”

“Why, indeed!” said he, in his natural tone. “But some emotion must appear to be raised by your reply, and surprise is more easily assumed, and not less reasonable than any other. Now let us go on. Were you never here before, madam?”

“Never, sir.”

“Oh Catherine, you must not divulge—” But the angel was not allowed to finish, since our heroine’s fingers moved a carafe of cream to block his/her/its view and simultaneously just slightly shove him out of the way.

“Indeed! Have you yet honoured the Upper Rooms?” continued Mr. Tilney.

“Yes, sir, I was there last Monday.”

“Have you been to the theatre?”

“No, she has not!”

“Yes, sir, I was at the play on Tuesday.”

“To the concert?”

“Yes, sir, on Wednesday.”

“And are you altogether pleased with Bath?”

“Yes—I like it very well.”

“Fie! No, she does not!”

“Now I must give one smirk, and then we may be rational again,” said Mr. Tilney.

Catherine turned away her head, not knowing whether she might venture to laugh, and also because she was widening her eyes very fiercely at one particular tiny figure of divine light that was leaping with animation and soon likely to topple into her teacup.

“I see what you think of me,” said the gentleman gravely—”I shall make but a poor figure in your journal tomorrow.”

“My journal!”

“Yes, I know exactly what you will say: Friday, went to the Lower Rooms; wore my sprigged muslin robe with blue trimmings—plain black shoes—appeared to much advantage; but was strangely harassed by a queer, half-witted man, who would make me dance with him, and distressed me by his nonsense.”

“Indeed I shall say no such thing,” said Catherine, thankful he knew hardly anything really about the true extent of nonsense or oddity a person could harbor, else he would not be referring thus to himself. . . .

“Shall I tell you what you ought to say?”

“If you please.”

“I danced with a very agreeable young man, introduced by Mr. King; had a great deal of conversation with him—seems a most extraordinary genius—hope I may know more of him. That, madam, is what I wish you to say.”

“But, perhaps, I keep no journal.”

“Perhaps you are balancing an angel on your shoulder”—(Catherine nearly choked)—“while I have the coiled tail of a serpent around mine—equally doubtful. Not keep a journal! How are your absent cousins to understand the tenour of your life in Bath without one? How are the civilities and compliments of every day to be related, unless noted down every evening in a journal? The various dresses to be remembered, the particular state of your complexion, the curl of your hair? My dear madam, I am not so ignorant of young ladies’ ways as you wish to believe me; it is this delightful habit of journaling which largely contributes to form the easy style of writing for which ladies are so generally celebrated. The talent of writing agreeable letters is peculiarly female. Nature may have done something, but I am sure it must be essentially assisted by the practice of keeping a journal.”

“Well! He is, mayhap, not such a fiendish fellow after all,” whispered Terence, or possibly Clarence. “Dangerous in his own way? Undoubtedly: anyone who ponders the craft of writing must somehow wield the potential, in the least, if not the secret power itself, to change the world. But malicious? Not this one. Dear child, we declare him to be a suitable companion . . .”

But our heroine never heard this advantageous analysis, so engrossed she was in the conversation of the moment.

“I have sometimes thought,” said Catherine, doubtingly, “whether ladies do write so much better letters than gentlemen! That is—I should not think the superiority was always on our side.”

“As far as I have had opportunity of judging, it appears to me that the usual style of letter-writing among women is faultless, except in three particulars.”

“And what are they?”

“A general deficiency of subject, a total inattention to stops, and a very frequent ignorance of grammar.”

“Upon my word! I need not have been afraid of disclaiming the compliment. You do not think too highly of us in that way,” said Catherine, unwittingly focusing her gaze upon a trio of angels that settled upon Mr. Tilney’s jacket lapel like a corsage of heavenly light.

“I should no more lay it down as a general rule that women write better letters than men, than that they sing better duets, or draw better landscapes. In every power, of which taste is the foundation, excellence is pretty fairly divided between the sexes.”

Catherine was momentarily thankful Mr. Tilney had never seen her horrid scrawlings of stick figures and monstrous ducks, else he might form a different, less balanced opinion.

They were interrupted by Mrs. Allen: “My dear Catherine,” said she, “do take this pin out of my sleeve; I am afraid it has torn a hole already; I shall be quite sorry if it has, for this is a favourite gown, though it cost but nine shillings a yard.”

“That is exactly what I should have guessed it, madam,” said Mr. Tilney, looking at the muslin, while Catherine fiddled with the pin in Mrs. Allen’s attire, finding not only a hole but an angel inadvertently entangled in it by a bit of thread, which had caused additional tearing and unraveling.

The angel exclaimed in dulcet tones, “Oh dear, oh dear!” as Catherine set it loose.

“Do you understand muslins, sir?” said Mrs. Allen meanwhile.

“Particularly well; I always buy my own cravats, and am allowed to be an excellent judge; and my sister has often trusted me in the choice of a gown. I bought one for her the other day, and it was pronounced to be a prodigious bargain by every lady who saw it. I gave but five shillings a yard for it, and a true Indian muslin.”

Mrs. Allen was quite struck by his genius. “Men commonly take so little notice of those things,” said she; “I can never get Mr. Allen to know one of my gowns from another. You must be a great comfort to your sister, sir.”

“I hope I am, madam.”

“And pray, sir, what do you think of Miss Morland’s gown?”

“It is very pretty, madam,” said he, gravely examining it; “but I do not think it will wash well; I am afraid it will fray.”

“How can you,” said Catherine, laughing, “be so—” She had almost said “strange,” then thought better of it, all things considered.

“I am quite of your opinion, sir,” replied Mrs. Allen; “and so I told Miss Morland when she bought it.”

“But then you know, madam, muslin always turns to some account or other; Miss Morland will get enough out of it for a handkerchief, or a cap, or a cloak. Muslin can never be said to be wasted. I have heard my sister say so forty times, when she has been extravagant in buying more than she wanted, or careless in cutting it to pieces.”

“Harrumph!” Catherine wanted to say, for no better reason than she felt she ought to—but held herself in check, due to the timely actions of an angel who lightly pinched her cheek before she could open her mouth and spoil the pleasantry.

Instead, it was Mrs. Allen who waxed eloquent: “Bath is a charming place, sir; there are so many good shops here. We are sadly off in the country; not but what we have very good shops in Salisbury, but it is so far to go—eight miles is a long way; Mr. Allen says it is nine, measured nine; but I am sure it cannot be more than eight; and it is such a fag[6]—I come back tired to death. Now, here one can step out of doors and get a thing in five minutes.”

Mr. Tilney was polite enough to seem interested in what she said; and she kept him on the subject of muslins till the dancing recommenced.

Catherine feared, as she listened to their discourse, that he indulged himself a little too much with the foibles of others.

“What are you thinking of so earnestly?” said he, as they walked back to the ballroom; “not of your partner, I hope, for, by that shake of the head, your meditations are not satisfactory.”

Catherine coloured, and said, “I was not thinking of anything.”

The angels never condoned her rare instances of uttering untruths; thus, it was a bit worrisome what they were likely to say—but for once Catherine was presented with complete angelic silence. Tiny glowing beings reposed on her sleeves, her shoulders, Mr. Tilney’s shoulders and lapels . . . and they simply regarded the two of them.

“That is artful and deep, to be sure; but I had rather be told at once that you will not tell me,” he persisted.

“Well then, I will not.”

“Thank you; for now we shall soon be acquainted, as I am authorized to tease you on this subject whenever we meet, and nothing in the world advances intimacy so much.”

They danced again, accompanied by a lovely whirling cloud of angels; and, when the assembly closed, parted, on the lady’s side at least, with a strong inclination for continuing the acquaintance.

Whether she thought of him so much, while she drank her warm wine and water, and prepared herself for bed, among the gentle whispers of her divine guardians, as to dream of him when there, cannot be ascertained. But I hope it was no more than in a slight slumber, or a morning doze at most.

For if it be true, as a celebrated writer has maintained, that no young lady can be justified in falling in love before the gentleman’s love is declared,[7] it must be very improper that a young lady should dream of a gentleman before the gentleman is first known to have dreamt of her.

How proper Mr. Tilney might be as a dreamer or a lover had not yet perhaps entered Mr. Allen’s head. But that Mr. Tilney was not objectionable as a common acquaintance for his young charge he was on inquiry satisfied. Indeed, early in the evening Mr. Allen had taken pains to know who her partner was, and had been assured of Mr. Tilney’s being a clergyman, and of a very respectable family in Gloucestershire.

However well that might be for Mr. Allen’s peace of mind, our heroine’s own was somewhat less secure. It is well known that pleasant twilight reveries are often followed by the coming of night and that which abides in it. And—dear Reader—in the darkness, dreams often turn to nightmares, just before the coming of the dance of thunder and lightning that accompanies heaven’s storm. . . .

Things were about to become very heroic indeed.

[1] Gentle Reader, not all Richards are “Poor” nor are they all “Dicks.”

[2] As opposed to a Windows mouse.

[3] The Astute Reader is surely stunned! But yes indeed, baseball is known and acknowledged by the Esteemed Author—possibly its earliest literary mention ever!

[4] A creature of nightmares, rumored to be first observed and harbored at a certain fine estate called Mansfield Park.

[5] It must be noted that some “last” volumes work better than others that actually precede the first volume in an endless series of imperial space battle rehashes, cute stuffed creature aliens and brother-sister pairings, strange forces that may or may not be with one—that is, ahem! Upon my word, what was that all about?

[6] Ahem! Gentle Reader, it is not what one thinks it is. Besides, there is nothing wrong with that.

[7] Vide a letter from Mr. Richardson, No. 97, Vol. II, Rambler. Verily dear Reader, young ladies in love must never divulge their delicate amorous state, for gentlemen are such flighty creatures, easily frightened out of their wits.

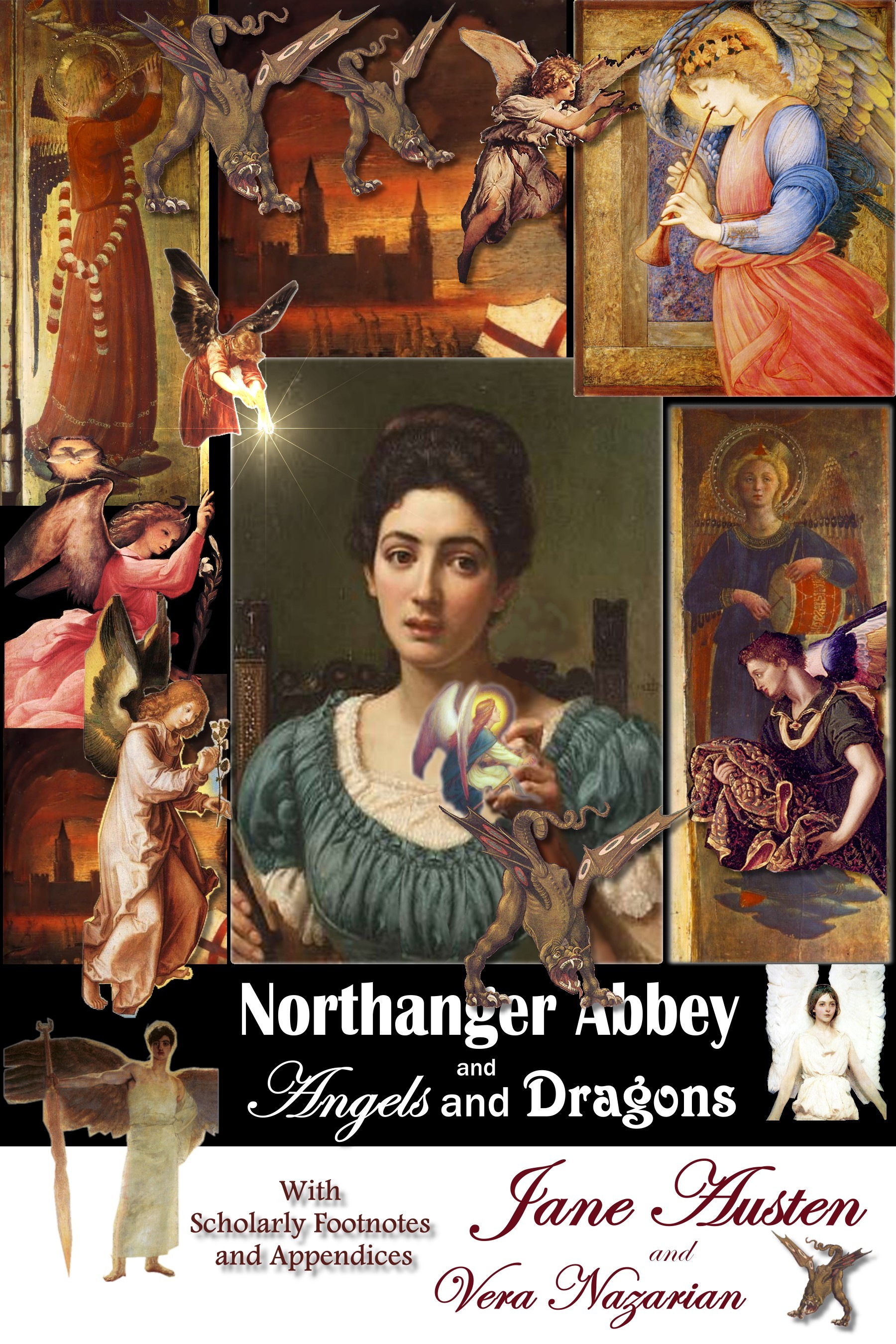

It is currently available in Trade Paperback and Kindle e-book format.

Please see the Official Northanger Abbey and Angels and Dragons Website for more information.